I suspect everyone knows the concept of inherent safety. Use a non-flammable instead of a flammable feed or make sure the system is designed so as to be unable to fail in a hazardous direction. Often, however, I encounter the reverse situation during a safety audit or a hazard analysis and risk assessment, an inherently unsafe mitigation that is ignored or unrecognized.

Get The Fire Extinguisher! Thoughts on Where to Locate Them for Maximum Safety

While the number of fire extinguishers required in an area is fire code driven, where to place them is primarily up to the designer or owner. Too often, the architect or building owner places them in the optimum location to minimize the quantity with no real thought for their utility in an emergency. Hence, a common question that arises is where should fire extinguishers be mounted from a safety perspective?

Are We Safe or Complacent?

A recent article in the ACS Chemical, Health, and Safety used extensive survey data to show that safety in academic and industrial research laboratories was improving. While a very interesting article, it struck a negative chord with me and raised an issue that forms the basis for this article. How does an organization know it is safe, that its safety culture, systems, and practices are effective? Assuming no recent spate of accidents has occurred can the organization assume it is safe or is it just complacent. I have written several articles on the overall subject (“We Are Comfortable with Our Current Safety Procedures”: How Do You Prevent Something You Don’t Recognize?, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/we-comfortable-our-current-safety-procedures-how-do-you-palluzi , “My Laboratory is Very Safe.”: The Dangers of Myopic Looks at Laboratory Safety, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/my-laboratory-very-safe-dangers-myopic-looks-safety-richard-palluzi).

Alarms versus Automatic Interlocks in Research Units

Alarms and automatic shutdowns are common in plants and on research units. Both have several shared functions, namely to keep a unit operating safely within design conditions. Both vary in others.

Alarms are intended to alert operating personnel to an impending problem in time for them to take appropriate corrective action. Automatic interlocks are designed to initiate the appropriate response when a predetermined limit or condition is reached. Often, they are used together. It is not uncommon to have a high temperature alarm to alert the operator to an impending interlock as well as a high temperature shutdown to cut off the power to the heater in the event the operator’s action did not bring the condition under control. Plants usually have one or more levels of alarm on every interlock. This gives operating personnel a change to intervene and try to correct the upset before the interlock automatically acts. Pilot plants, laboratory units, and research equipment often have only one of the other (or occasionally, neither).

Laboratory and Pilot Plant Safety Audits: How to Use Them to Avoid Accidents and Improve Safety Performance

Laboratory and pilot plant safety audits are an important and often overlooked tool for improving an organization’s safety awareness and performance. An audit, unlike a routine safety inspection, is something that occurs less frequently and generally should utilize outside personnel (a ‘cold eyes” type review). It’s purpose is to let someone else review your equipment, facilities, and programs and offer their advice on areas that appear to need improvement or that may be being overlooked or their hazards unrecognized. The fact that the personnel doing the audit come from outside the organization allows then to look at your routine activities in a different light. This new perspective often highlights issues that escape everyone’s attention, no matter how committed nor how diligent.

Where is the Best Place to Put a Flammable Storage Cabinet?

Generally anywhere. However, there are a few places a flammable storage cabinet should not be placed. These include:

So that they obstruct an exit door. The flammable storage cabinet should never infringe on the doorway, however minor, nor impede the opening of the door itself.

- So that they obstruct any fire exit egress. Mandated fire egress routes are clearly defined in the facility plans. In most cases, they are posted on walls to show the occupants the best way out. These exits cannot be narrowed no matter how wide. So, if the egress, typically a corridor, is 6 or even 8 feet wide you cannot narrow it at any point. Hence you cannot place a flammable storage cabinet in any of these corridors. (This is true for anything in these egress routes, not just flammable storage cabinets.)

- In a stairwell that is part of a fire exit.

Any of these cases would be a violation of OSHA 29 CFR 1910.106(d)(5)(i), NFPA 1, and NFPA 101.

Transporting Compressed Gases and Cryogenic Dewars On an Elevator

One hopes that no one is going to try and hoist a compressed gas cylinder on their shoulder and attempt to carry it up or down a flight of stairs to another floor. Similarly, one hopes no one is going to try and pull a cryogenic dewar up down the stairs to another floor. (And yes, the published story of the sad results of one test of this methodology at a leading California school is available. I suspect there are several others less well known.) So that leaves using an elevator to move these bulky and heavy components to higher or lower floors of a laboratory.

Is it safe to use that procedure?

Scared Safe: The Importance of Human Error when Evaluating Research Operations for Safety

THazard analysis and risk assessment (HARA) of research operations often does not adequately consider the possibility for human error to potentially create a hazard. The problem is that humans can do anything wrong, in any way imaginable (and some not readily imaginable) at any time. Unlike equipment which has common failure modes, human failure modes are almost totally unpredictable and so, difficult to determine with any certainty.

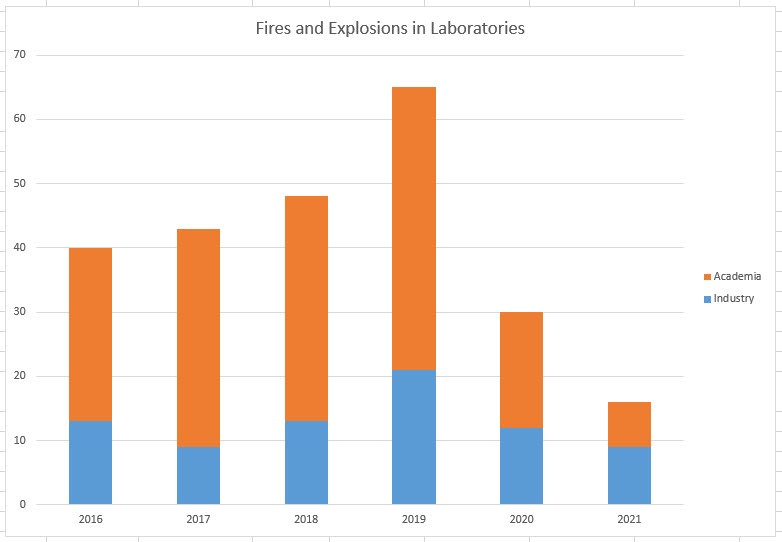

Laboratory Accidents

I’d like to believe safety in Laboratories is improving. On the surface that is what this graph shows.

Sadly, considering the impact COVID had on laboratory operations in most of 2020 and continues to have through the first part of 2021 I suspect that is not the case. Rather it just represents the downturn in laboratory operations during the pandemic. Fewer people working in laboratories results in fewer accidents.

“We Are Comfortable with Our Current Safety Procedures”: How Do You Prevent Something You Don’t Recognize?

When I am asked to consult on safety issues or provide safety training for laboratories and pilot plants, I usually suggest starting with a safety audit of the facility or operation to determine what are the areas that require attention. Limited resources, tight funding, other priorities are among the most commonly cited reasons for deferring any audit to a later date and just focusing on the specific question I was asked. All these reasons are valid constraints but bad reasons. Limited resources, tight budgets, and multiple (and usually divergent) priorities make it critical to determine what are the potential safety issues so as to allow them to be addressed in a priority order using the limited means available.